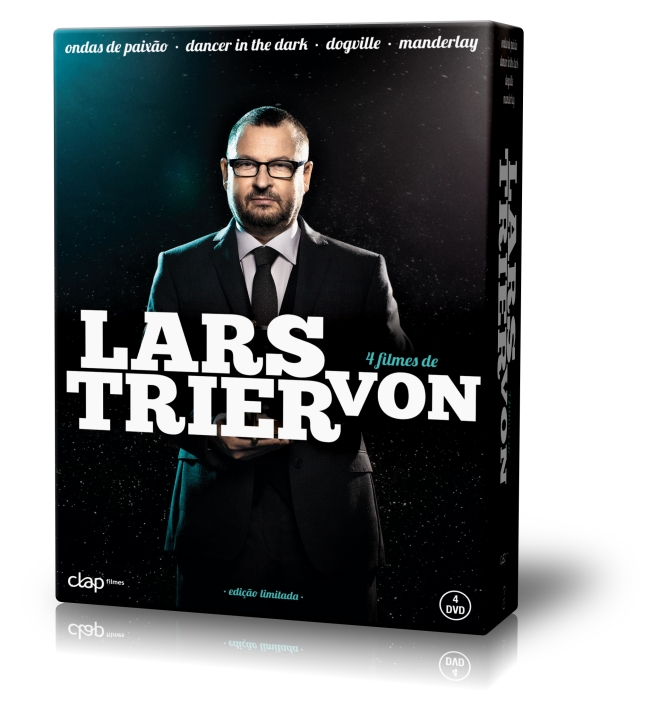

Lars Von Trier: Gênio ou Fraude? (por Linda Badley)

“Lars Von Trier – genius or fraud?” – asks a May 2009 Guardian Arts Diary poll. Its subject is arguably world cinema’s most confrontational and polarizing figure, and the results: 60.3% genius, 39,7% fraud.

Trier takes risks no other filmmaker would conceive of (…) and willfully devastates audiences. Scandinavia’s foremost auteur since Ingmar Bergman, the Danish director is “the unabashed prince of the European avant-garde” (IndieWIRE). Challenging conventional limitations and imposing his own rules (changing them with each film), he restlessly reinvents the language of cinema.

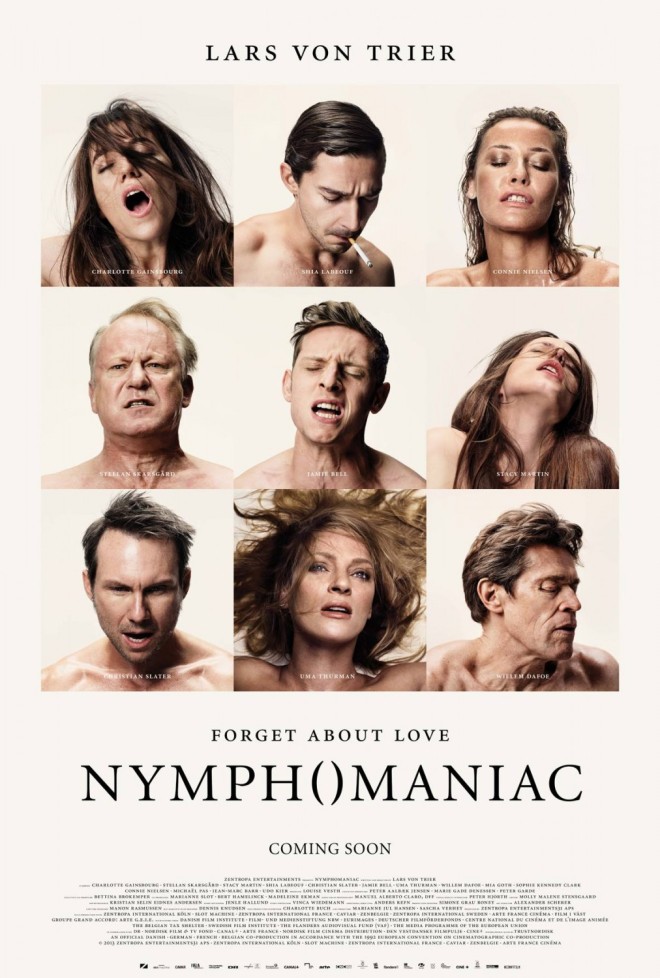

Personally he is as challenging as his films. After having written some of the most compelling heroines in recent cinema and elicited stunning, career-topping performances from Emily Watson, Björk, Nicole Kidman, and Charlotte Gainsbourg (photo), he is reputed to be a misogynist who bullies actresses and abuses his female characters in cinematic reinstatements of depleted sexist clichés.

He is notorious at Cannes for his provocations and insults, as in 1991, when he thanked “the midget” (Jury President Roman Polanski) for awarding his film Europa third, rather than first, prize. Some years later, at Cannes, in a scene worthy of Michael Moore, he called U.S. President George W. Bush an “idiot” and an “asshole”, lending vituperation to the already divisive Manderlay (2005), his film about an Alabama plantation practising slavery into the 1930s…

Coming from a small country infiltrated by America’s media-driven cultural imperialism, he has found it not merely his right or duty to make films about the United States but impossible to do otherwise. Despite that, Von Trier is known for his celebrated refusal or inability (he has a fear of flying) to set foot in the United States…

A similar effrontery had provided the catalyst for Dogme 95, the Danish collective and global movement that took on Hollywood in the 1990s and continues to be well served by the punk impertinence of the Dogme logo: a large, staring eye that flickers from the rear end of a bulldog (or is it a pig?).

Dogme shows where the provocateur and auteur come together. Claiming a new democracy in which (in the manifesto’s words) “anybody can make films”, Trier and the Dogme “brothers” market out a space for independent filmmaking beyond the global mass entertainment industry. Although he rarely leaves Denmark, he has cultivated a European and uniquely global cinema. Making his first films in English, he quickly found a niche in the international festival circuit. He drew inspiration from a wide swath – from the genius of Andrei Tarkovsky to movements such as Italian neorealism and the international New Waves of the 1960s-1970s, to American auteurs Stanley Kubrick and David Lynch…

Trier’s long-term affinity with German culture – from expressionism and New German cinema to the writings of Karl Marx, Franz Kafka, and Friedrich Nietzsche – extends to equal passions for Wagnerian opera and anti-Wagnerian (Brechtian) theater… In spite of his flaunted internationalism, Trier has become the standard-bearer for Nordic cinema. Like Bergman and Carl Th. Dreyer, whose visions transcended nationality, he has exploited Scandinavian “imaginary” – bleak landscapes, Lutheran austerity and self-denial, the explosive release of repressed emotions – to project it elsewhere. He has similarly appropriated the Northern European Kammerspiel (chamber play) that Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg had condensed into a charged medium.

Reincarnating Dreyer’s martyrs (The Passion of Joan of Arc, 1928; Ordet, 1955) and the anguished female performances of Bergman’s films for the present era, he has invented a form of psycho-drama that traumatizes audiences while challenging them to respond to cinema in new ways.

His interest in theater goes back to his youth, and his films are theatrical in several senses: stylized, emotionally intense, and provocative. His features have invoked 20th century theatrical initiatives clustered under the heading of the performative: especially Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, Allen Kaprow’s “happenings”, and Guy Debord’s situationism, which reformulated Marxist-Brechtian aesthetics for the age of the “spectacle” in which power, concentrated in the media image, turns individuals into passive consumers. In 1952, Debord called for an art that would “create situations rather than reproduce already existing ones” and through the performance of “lived experience” disrupt an expose the spectacle. In 1996, Trier similarly explained his view of cinema-as-provocation: “A provocation’s purpose is to get people to think. If you subject people to a provocation, you allow them the possibility of their own interpretation” (Tranceformer). (…) The films bear witness, make proclamations, issue commands, pose questions, provoke responses… Thus his films have had an impact on their surrounding contexts, affecting audiences, producing controversies, and changing the aesthetic, cultural, and political climate of the late 1990s an the 2000s.”

By Linda Badley.“Making The Waves: Cinema As Performance”.

University of Illinois Press. 2010.

* * * *

You might also enjoy:

Thomas Vinterberg is the co-creator, together with Lars Von Trier, of Dogme 95. Linda Badley remembers that Dogme 95 “required abstinence from Hollywood-style high tech cosmetics, calling for an oppositional movement with its own doctrine and ten-rule “Vow of Chastity”. Coming up with the infamous rules was “easy”, claims Vinterberg: “We asked ourselves what we most hated about film today, and then we drew up a list banning it all. The idea was to put a mirror in front of the movie industry and say we can do it another way as well.”

– Post reblogado do Awestruck Wanderer

Publicado em: 21/04/14

De autoria: casadevidro247